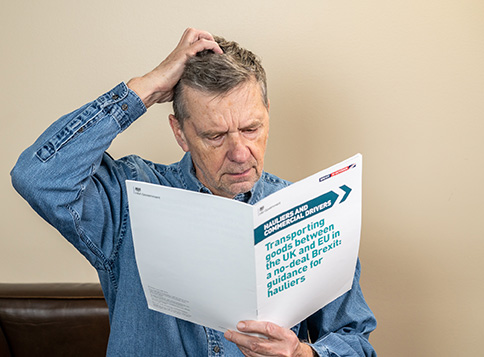

Decision by majority of British electorate creates confusion

By Canute James *

The decision by the majority of British voters to support the country’s divorce from the European Union has caused significant confusion in the UK and in the Caribbean. Former UK prime minister David Cameron’s political career was ended by a result he clearly did not expect.

But, there was confusion also among the leaders of the “Leave” movement. Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage could not deliver any coherent policy to address a result that they, too, appeared not to expect.

But, there was confusion also among the leaders of the “Leave” movement. Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage could not deliver any coherent policy to address a result that they, too, appeared not to expect.

The first reactions in the region to the historic 2016 Brexit vote concerned the economic ties with the European Union and with the UK. These links have developed as a consequence of the region’s colonial history and have been structured and formalised in a series of trade treaties such as the Yaoundé Agreement, the Lomé Convention, the Cotonou Agreement and the Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA).

The result of the UK’s June 23 referendum has also allowed the appearance of ghosts of the Caribbean past. Latent and doubtful sentiments about regional cooperation have been given voices that have suggested that perceived difficulties can be resolved only by abandoning struggling efforts at regional economic cooperation. They suggest that, like the UK’s decision to leave the EU, members of the Caribbean Community (Caricom) should seek to become independent of the group.

A former foreign minister of Jamaica, Oswald Harding, argued that his country’s links with Caricom should be decided by a referendum, rather than by politicians. He referred to the debate about Jamaicans having difficulty entering some Caricom countries as a violation of the free movement of people agreement which, he said, is a fundamental part of Caricom.

Another former Jamaican foreign minister, K.D. Knight, said a referendum is not the method that should be used to determine continuing membership of Caricom. These issues, he said, should be determined through diplomacy.

Considerations and re-considerations across the region are, perhaps, inevitable, given its history of efforts at cooperation and collaboration: from the attempt at a political federation, through the continuing debate about the Caribbean Court of Justice, to the apparent abandoning of the move towards a single economy with the concentration instead on achieving a single market.

A Caribbean advantage?

Rather than creating doubts over the prospects for regional economic and functional cooperation, the Brexit vote can be to the Caribbean’s advantage, argued University of the West Indies vice chancellor Sir Hilary Beckles.

“Every aspect of Caribbean life will be adversely affected by this development: from trade relations to immigration; tourism to financial relations; and, cultural engagements to foreign policy,” he said.

“Caricom should use this development in order to deepen and strengthen its internal operations and external relations to the wider world. It is a moment for Caricom to come closer together rather than drift apart. The region should not be seen as mirroring this mentality of cultural and political insularity but should reaffirm the importance of regionalism within the global context for the future.”

Given the history of trade and other economic relations between the region and the EU, it is inevitable that the more immediate assessment of the Brexit vote has ben focused on these aspects. But the uncertainty about the likely impact is compounded by the absence of a known schedule for the UK and the EU to negotiate the disengagement.

“The master agreement with the EU will remain in place, including with the UK, until the divorce terms have been settled and, who knows, they may fall in love again,” said the Inter-American Development Bank’s regional economic advisor for the Caribbean, Inder Ruprah. “Uncertainty always has a negative impact on economic growth and economics in general but we are talking about two years, three years, four years before any kind of negotiation could go ahead.”

The EU is not the region’s major trading partner, although the UK market is important to the Caribbean, said the University of the West Indies’ pro vice chancellor for global affairs, Richard Bernal. “The negotiations for the exit are likely to take several years which means the EPA remains in place. Built into that agreement are various institutional arrangements to review and recalibrate the agreement. When the UK does in fact leave that agreement, I see no reason why the agreement has to be renegotiated. Britain has dropped out and will not be applying it.”

Former prime minister of Jamaica, Bruce Golding, is also downplaying an immediately negative economic impact on the Caribbean from the Brexit decision. The region’s trade with Europe has been “anemic,” he said. “In any event, most of the agreements we have signed are with the EU and not Britain. And these should not be adversely affected.” New agreements may have to be negotiated with the UK, he said. “Even with Haiti and the Dominican Republic included in Caricom, we are a small economic space and so we have to look beyond to Latin America to get the critical mass needed to be a real force.”

But the real impact of the Brexit vote on the region will also be determined by the performance of the British economy. Already pensions and private remittances from the UK to the Caribbean have been depressed because of the devaluation of the British pound. A weaker pound will also deter UK tourists holidaying in a region in which hotel rates are denominated in US dollars.

And inevitably some sectors will fare better than others. Guyana’s gold industry is reaping benefits of higher global prices as uncertainty is driving investors to the safe haven provided by the metal. []

- First published on November 1, 2017

* Canute James, PhD, Adjunct Senior Lecturer and former Director of the Caribbean Institute of Media and Communication (CARIMAC), Mona Campus, University of the West Indies, was a reporter for the Financial Times of London and radio reporter, presenter and producer in London, England for the BBC.