Prepare for disaster with Oil Spill Contingency Planning

By Jesper Goodley Dannisøe and Jan Sierhuis

Oil in the sea can be disastrous especially for living organism and animal life. Even a relatively small oil spill can create quite a mess, affecting beaches and habitats. What actually happens when an oil spill hits the port or the shoreline? What can port managers do to limit the damage? How can the limited resources available be used most effectively in dealing with this disaster? The answers to these questions require current insight into the trajectory of oil spills under different circumstances, as well as a clear understanding as to what are the most sensitive at-risk areas and how to mitigate such risks. An effective communication strategy which addresses risks, sensitivities and response strategies is a crucial part of any successful oil spill contingency plan. – Ed.

Oil spills are unpredictable in nature simply because they are always incident-based. They therefore share few similar characteristics. Oil spills may result from two major sources: leaking from ships en route or spilled during fuelling operations in the port.

The volume and type of oil released will differ from one incident to another. The first type of incident, leaking from a ship, is difficult to predict, as there is no limit to where it is likely to take place. If the spill is not in (or close to) a port, clean-up will, most likely, be the responsibility of the national environmental authorities. However, if the spill is close to a port, the responsibility may be that of the port or, otherwise, the joint responsibility of both port and public authorities.

Potential oil spills

If the spill happens in the port, the responsibility for control and clean-up will most likely rest with the port authority but may also involve all relevant authorities. Regardless of who is responsible it is recommended that the national authorities and the port authority find a common platform for building a response/contingency team, capable of combatting oil spills. Contingency plans should include knowledge about the physical and chemical properties of various types of oil, including toxicity, evaporation etc. However, it is also important to understand the transport mechanisms of oil, which to a large extent, are driven by meteorological conditions.

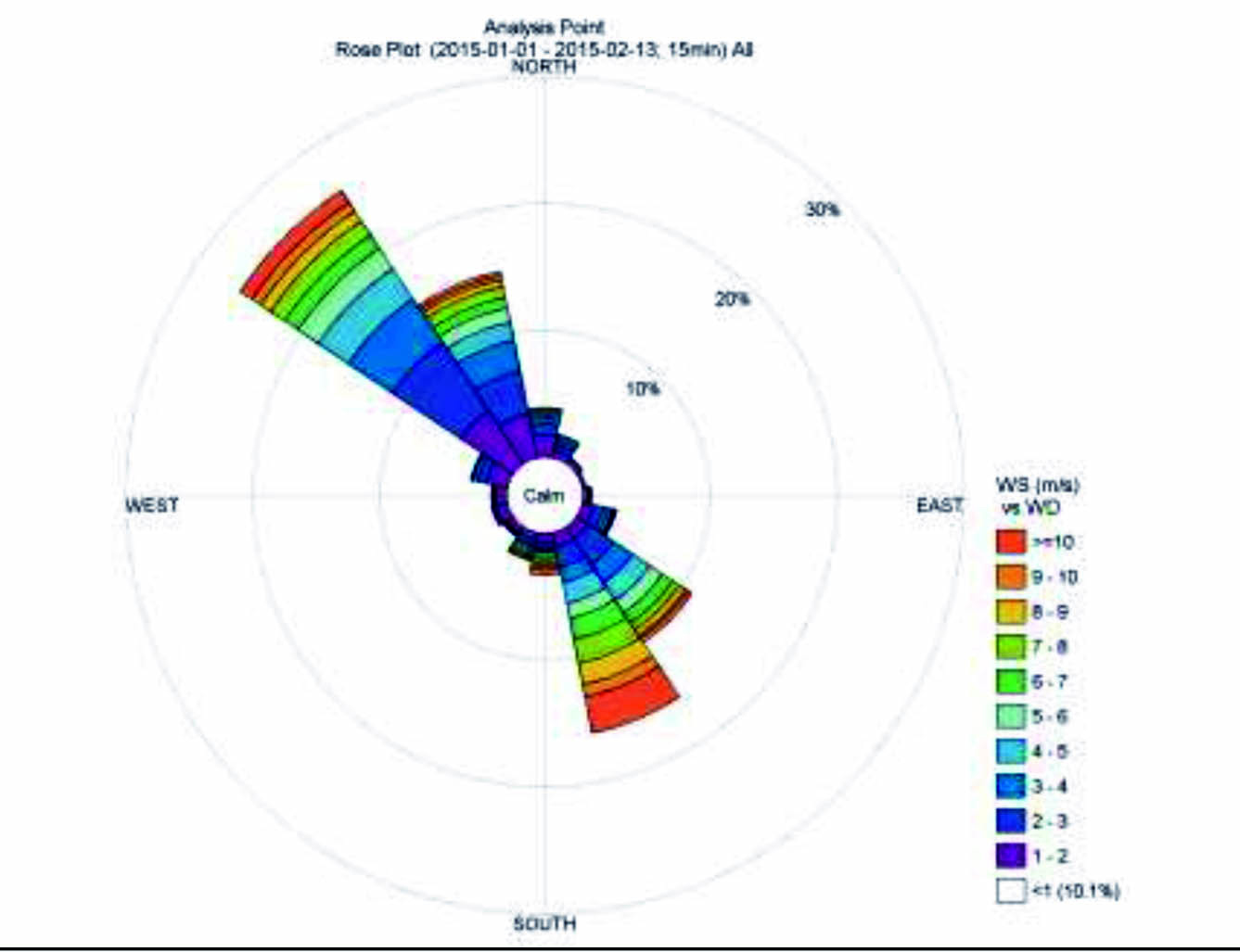

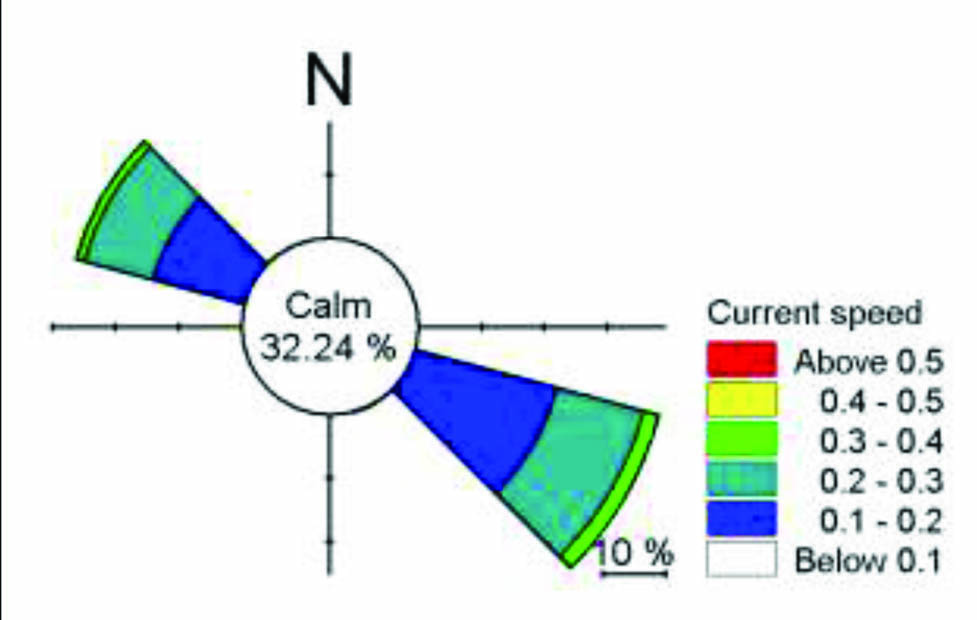

Many larger ports in Europe have conducted studies to assess an oil spill under various meteorological conditions. They have built up decision-support systems that enable the port authorities to launch proper measures to contain and limit the extent of a spill. The decision-support systems are often based on numerical modelling tools, where several scenarios under different weather conditions have been tested. The results can then be used during a spill, where size and position as well as prevailing meteorological conditions can be combined and used to deploy the best possible response to reduce impact. Important tools for predicting the state and direction of a spill are wind and current roses for a number of points along the coast. We recommend that meteorological and hydraulic measurements are carried out at different places to enable the development of roses for the different seasons, as the local climate condition may show large seasonal variation.

Containing, managing spills

Based on knowledge about the potential trajectories for a specific oil spill, it is up to the authorities to employ the right measures to reduce the impacts as much as possible. It is important to quickly gather information about the type and volume of oil in the spill; whether the spill is limited to a simple incident or if the oil is constantly being released from a ship or a land-based container; and whether the discharge will stop after a short or a long period. Oil will gradually be degraded by natural processes over time and therefore the various measures to reduce the impact from an oil spill should take the natural degradation into account. For light oil, the natural degradation may take just hours or days, whereas heavy fuel oils may take years to degrade and it may be necessary to use chemical agents to accelerate degradation.

If the trajectory indicates that the plume of an oil spill will move out in the ocean, one of the best measures is to leave the oil and let the natural processes take care of the degradation. This should only be considered if it is light oil. However, leaving oil to drift to sea is only an option if it does not return shortly after by tidal or diurnal current changes.

If the oil spill is drifting towards land the responsible authority must take action to either prevent the oil from reaching land or, if possible, route the oil towards a place where the damage will be less. A wide variety of oil booms and other materials are available but, for most of these, they only work properly for smaller spills and only if they are deployed very quickly after the release of the oil. If the authorities are successful in containing or controlling the spill, there are various types of oil skimmers that can be used for collecting the oil. However, it must be borne in mind that the thickness of an oil spill (from centimetres to less than 1/1000 of a millimeter) and the physical conditions of the oil may make it very difficult to collect. Most response systems only work properly in calm weather. And if an oil spill takes place during windy or stormy conditions, very few if any of the response systems work properly.

In some situations, the only possibility is to use dispersants, which act by breaking the oil up into droplets, which are easier to degrade. However, dispersants may also make the oil sink to the bottom and therefore it is a big advantage if the authorities have seabed maps available so that they can decide whether the oil sinking to the bottom will cause substantial damage to specific types of vulnerable seabed creatures or structures, for example, deep sea corals.

If the oil ends up on the shore, the clean-up work will be time-consuming and very expensive. Injury to birds, turtles and other species will be extensive and recovery and a return to normalcy could take a long time.

Sensitivity maps

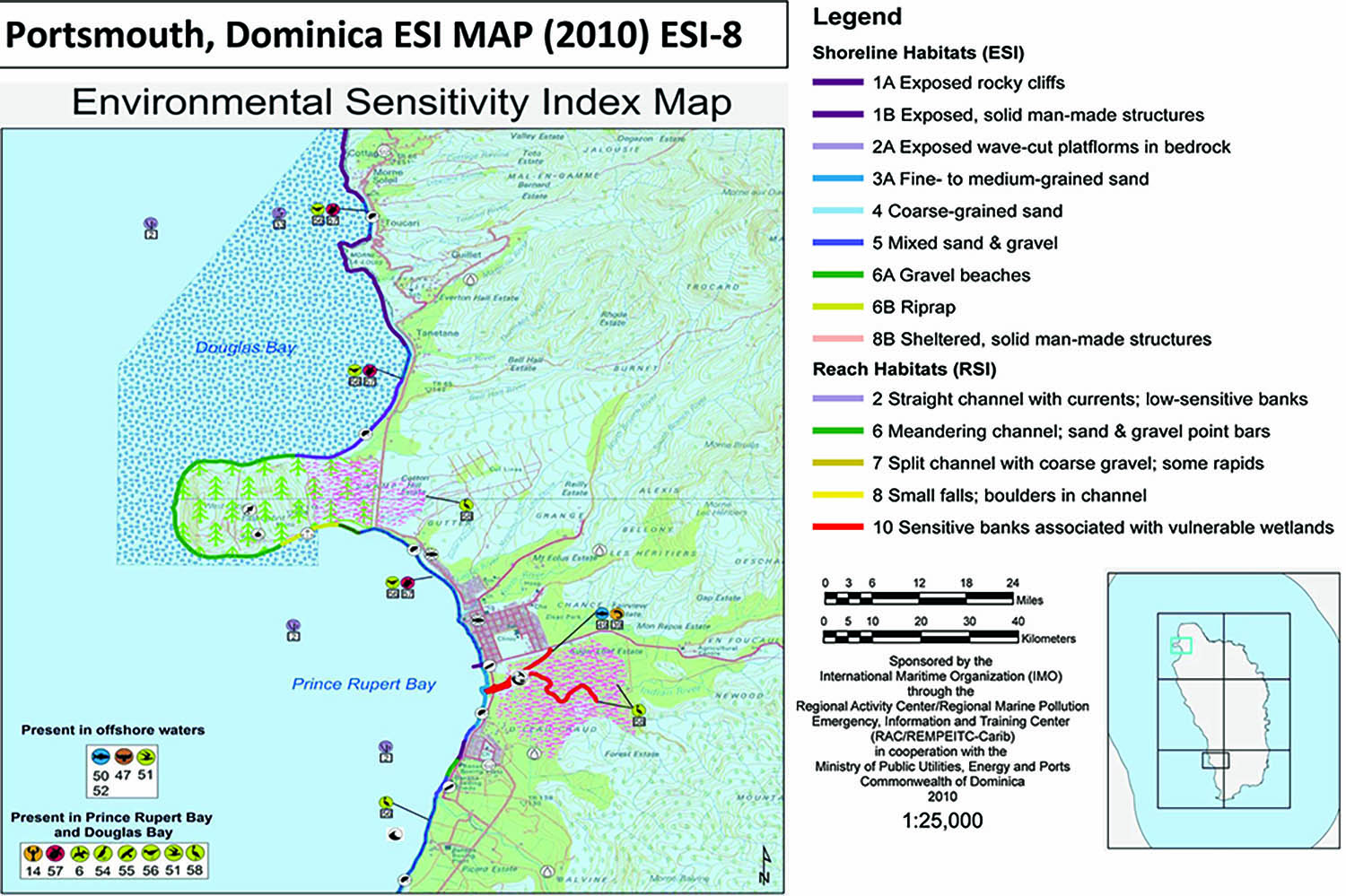

Environmental Sensitivity Index (ESI) maps are a useful planning and operational support tool to develop an oil spill response strategy. They may contain critical infrastructure, protected areas, important biodiversity areas, critical habitats, endangered species and key natural and human resources. They are labeled sensitive because they are: (1) of critical environmental, economic, or cultural importance; (2) at risk when coming into contact with spilled oil; and, (3) indirectly affected by a spill.

The maps are used to support the development of a prioritized response strategy and they should be part of the oil spill contingency plan. They enable managers to determine the most sensitive areas and resources, providing a basis for the definition of priorities for protection and clean-ups, and to determine the most cost-effective response strategy. During actual response operations, these maps will be used by decision-makers to set the priorities for protection by on-scene commanders for the organization of the response operations and by on-site responders for site specific response actions.

The response actions depend on the specific conditions and local circumstances and on the scale of the spill. Contingency plans classify oil spills into three different ‘categories’:

- Tier I spills – smaller spills, mostly related to an operational activity at a fixed location or facility, usually handled by the facility operator;

- Tier II spills – larger in size and geographical spread, requiring additional resources from

a variety of potential sources (e.g. a port authority), involving more stakeholders;

- Tier III spills – large scale spills with major impact, requiring substantial resources on the national and/or international level.

The International Petroleum Industry Environmental Conservation Association (IPIECA), jointly with the International Maritime Organization (IMO), published a guide for “Sensitivity Mapping for Oil Spill Response” in 2012. This guide distinguishes between three types of sensitivity maps: Strategic sensitivity; Tactical sensitivity; Operational sensitivity.

Strategic sensitivity maps are used by decision-makers for Tier II and III oil spills, to establish priorities for protection and clean-up, prioritizing the most sensitive areas. They synthesise information with the objective of locating and prioritising the most sensitive sites; reinforce the response capabilities for these sites; and, resolve the issue of competing priorities in the case of limited protection and clean-up resources available.

Tactical sensitivity maps are used as a general planning and response tool during an incident by on-scene commander and the incident command post. These provide responders with environmental, socio-economic, logistical and operational information on the site and the response operations.

Operational sensitivity maps are for the most critical areas. These include site-specific information on logistical and operational resources available and response strategies and limitations for on-site responders.

Sensitivity mapping in the Caribbean

Within the framework of the Cartagena Convention and the Oil Pollution Preparedness, Response and Cooperation (OPRC) Convention, the Caribbean is identified as a special high-risk area because of the high presence of the oil industry and tanker traffic and due to the unique environmental and economic value of the Caribbean Sea and the coastlines of Caribbean nations.

Priority efforts are undertaken by IMO and UNEP to implement effective oil contingency plans in the region and sensitivity maps are deemed an essential tool for this purpose. The Curaçao-based Regional Activity Centre RAC/REMPEIT-C is one of the support agencies used to assist Caribbean governments and ports with oil contingency planning and sensitivity mapping.

Figure 3 is an example of a modern Environmental Sensitivity Index (ESI) Map, produced for the Commonwealth of Dominica. It shows ESI Map 8 of the coastal area of Portsmouth.

Community-based mapping and planning

No matter how ‘state-of-the-art’ your tools, maps and plans are, if they are not produced in cooperation with all port and national stakeholders and relevant community groups they are not likely to work well during an oil spill. Responders must learn to define and set their priorities in community-based terms instead of port and maritime jargon, especially for Tier II and Tier III spills.

Involve the community and the media in plans and priorities and engage them in all drills, exercises. The support of the media and the wider community is required for plans to be effective. []

- First published June 1, 2016

Jesper Goodley Dannisøe, Senior Project Manager, DHI Denmark (jda@dhigroup.com)

Jan Sierhuis, Director, Maritime Authority of Curacao (maritimecuracao@gmail.com)