Reality, consequences and preparedness strategy

By Ibrahim Ajagunna and Fritz Pinnock

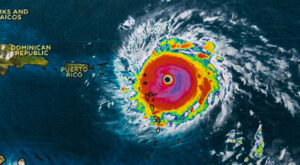

In most Caribbean islands, over fifty percent of economic assets, including seaport facilities, are concentrated in coastal areas. The region is highly prone to natural disasters and tropical storms, often in the form of hurricanes, are annual, cyclical and, to some extent, predictable. Tropical storms and hurricanes often cause additional disasters including landslides and flooding.

Over the past 25 years, natural disasters have cost the region billions of dollars in damage, with an attendant negative impact on economic health and development. Even more devastating is the human suffering and dislocation which prevail long after the disasters have occurred.

Experts have argued that there is a bi-directional relationship between shipping and natural disaster. It is claimed that shipping contributes to carbon loading and global warming and that global warming, in turn, contributes to natural disasters. Long haul travel by ships is particularly carbon intensive and the resultant change in climatic conditions has negative implications for the shipping industry.

All Caribbean islands are vulnerable to the impacts of natural disaster because of a number of factors including geographical location along the tropical storm path, which sweeps from the west coast of Africa to the West. Given the importance of the shipping industry to future growth and development of the Caribbean, it is important to monitor and evaluate potential risks and impacts of disaster to the industry.

More than twice

More than twice

In 2004, a number of Caribbean islands were affected by different hurricanes. Some islands were hit more than twice. See below:

- May 2004 – Floods in Dominican Republic and Haiti

- August 2004 – Hurricane Charley in Jamaica, Cayman Island and Cuba

- August 2004 – Hurricane Frances in Dominican Republic, Turks and Caicos and Bahamas

- September 2004 – Hurricane Ivan in Grenada, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Jamaica, Cayman Islands, Cuba and Mexico

- September 2004 – Hurricane Jeanne in Haiti, Dominican Republic and Bahamas

The 2004 hurricane season tragically demonstrated the Caribbean region’s exposure and vulnerability to this particular type of weather event. The hurricanes and tropical storms that devastated Grenada and parts of Cuba, Jamaica, Haiti, Dominican Republic and the Bahamas claimed more than 3,000 lives. In addition, some 2,000 people perished in floods in South-eastern Haiti during the hurricane season. In Guyana, the most severe floods recorded in more than 100 years devastated the coastal areas in January 2005, catching whole communities off guard. Since then, between 2005 and 2014, a number of hurricanes have affected many of these islands.

Natural disasters can affect long-term outcomes through a number of channels, including seashore line, agriculture and by creating environmental damage. The destruction of shipping ports, for example, could have a long-lasting negative impact on the following:

- Stock and volume of port operations

- Reconstruction efforts, which could crowd out productive capital expenditure

- Increased indebtedness

- A worsening of fiscal and external balances, which could create inflation and even trigger a financial crisis.

Consequences

Every year over 100 tropical depressions or potential hurricanes are monitored. However, on average, only ten reach tropical storm strength and six ultimately become hurricanes.

Shoreline erosion has been a problem. In Jamaica, it is estimated that 50% of the beaches have been seriously eroded by hurricane and storm surges, with the northeast coast being the most affected. An estimated 60% of all the trees in the mangrove areas have been lost, 50% of the oyster culture was unsalvageable and un-measurable harm came to coral reefs.

In Grenada, between 2004 and 2005, tropical storms and hurricanes wiped out 90% of the country’s nutmeg trees. Nutmeg and its by-product mace at that time accounted for 22.5 % of Grenada’s merchandise exports.

In 2007 hurricane Dean destroyed more than 80% and (in some areas as much as 100%) of the banana crop in St. Lucia, Martinique, Dominica and Guadeloupe.

Studies show that, in Antigua and Barbuda, Belize, Guyana and Panama, more than 50% of merchandise exports comprise food; while in Aruba, Nicaragua and St. Vincent and the Grenadines this figure is above 80 %. In most Caribbean islands the agriculture sector employs a significant portion of the workforce, the majority of whom are regarded as being below the poverty line. Agriculture in Jamaica, Panama and Cuba employs about 20% of the workforce.

The Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region has sustained devastating losses and fragmentation of families and communities over the past decades: from 1970 to 2000, natural disasters caused an estimated yearly average of 7,500 deaths, with an estimated annual average cost of between $700 million and $3.3 billion (Charveriat, 2000).

Healthy ports are at the economic heart of the areas they serve; this is especially true for island-nations in the LAC, as they are heavily dependent on international trade. The tragic aftermath of Hurricane Georges also illustrates the cascade of problems that can follow in the wake of damage to ports. Georges, a category 4 hurricane, swept through the LAC and the U.S. in 1998, killing 604 people and causing nearly $6 billion in property damage and sadly, crippled ports delayed humanitarian aid to needy areas.

Damage to ports can impede response and recovery activities immediately following a disaster. But, damage to the port can also impact the entire society and the region for years following a disastrous event. The overarching issue however is that the majority of these countries were former colonies whose sole purpose was to supply agricultural raw materials to the colonial powers. The national economies are largely built on the continued exports of these commodities. The consequence here is that, natural disasters of any type have both direct and indirect impacts on the shipping industry and invariably the ports that facilitate shipping.

Preparedness strategy

- Coping With Risk Through Insurance and Capital Markets: Insurance can reduce the negative impact of natural disasters by spreading the burden over space and time. Natural disasters are “high severity, low frequency” events that are more difficult to manage for insurance companies than the “low severity, high frequency” risk that they prefer to cover. In addition, objective information on damage and risks is difficult to obtain. It is argued that, the market for catastrophe risk insurance is well known to be inefficient, with high price of coverage, excessive volatility and insufficient pooling of risk. As such, a more efficient risk-sharing procedure would use capital markets to spread the exposure over a larger number of investors.

- International Assistance and Cooperation: External assistance plays an important role in helping countries mitigate the effects of exogenous shocks. An increasing share of official development assistance is being devoted to emergency assistance. And multilateral financial institutions are also doing more in this area. Nevertheless, the very rapid increase in the frequency of natural disasters around the world suggests a need for increasing the effort. In addition, the majority of external assistance for natural disasters has been concentrated on a few very visible events. And it is possible that smaller disasters getting little media coverage are receiving too small a share of assistance. Given the small individual amounts of assistance, cooperation among agencies is important to ensure that resources are distributed appropriately.

Other strategies for Caribbean ports would include:

-

- A regional recovery plan by participating ports

- The promotion of a comprehensive integrated disaster plan

- Regional institutional disaster training and research

- Enhancement of monitoring and early warning systems

- Regional focal point for comprehensive disaster management

In addition, the Revised Treaty of Basseterre (RTB) which entered into force on January 21, 2011, provides for establishment of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) Economic Union as a single financial and economic space within which goods, services, people and capital move freely (Article 4 of the RTB). The establishment of the Eastern Caribbean Economic Union (ECEU) Protocol also establishes a Customs Union which provides for free circulation of goods. It is interesting that the seven members and two associate members are looking into the possibilities of establishing a single port authority to regulate all member ports as they have successfully done with a single aviation authority.

This will not only reduce overheads but improve port resilience strategies as there will be multiple entry and exit points into a larger 600,000 population space offering greater economies of scale and flexibility. In this regard, these physically smaller territories are leading the way for many larger economies in the rest of the Latin America and the Caribbean.

Synergy

The Caribbean shipping industry’s vulnerability is determined by a dynamic set of factors, which include natural disasters, economic structure, stage of development and prevailing economic and policy conditions. Regardless of the type of fix, the complexity of ports and the great number of stakeholders involved mean that any effective effort to improve port resiliency will require complex interactions among many partners: the owners and operators of the port, its regulators, the financial sector, port-users and out-of-the ordinary users such as humanitarian organizations.

Given this complexity, public-private partnerships that incorporate multiple stakeholders can create a synergy that can yield great advantages for port resiliency (Smith, Mothering & Link, 2013).

To understand and assess the consequences of natural disasters and their implications for policy, it is important for Caribbean ports to consider the pathways through which different types of disasters impact on each state; the different risks posed; and, the ways in which ports adapt to or mitigate potential threats to quick recovery. []

- First published: June 1, 2016.

- Ibrahim Ajagunna, PhD, FCILT is Director of Academic Studies, Caribbean Maritime Institute.

- Fritz Pinnock, PhD, FCILT is Executive Director of the Caribbean Maritime Institute