Challenges for Caribbean port operators

By Franklin McDonald*

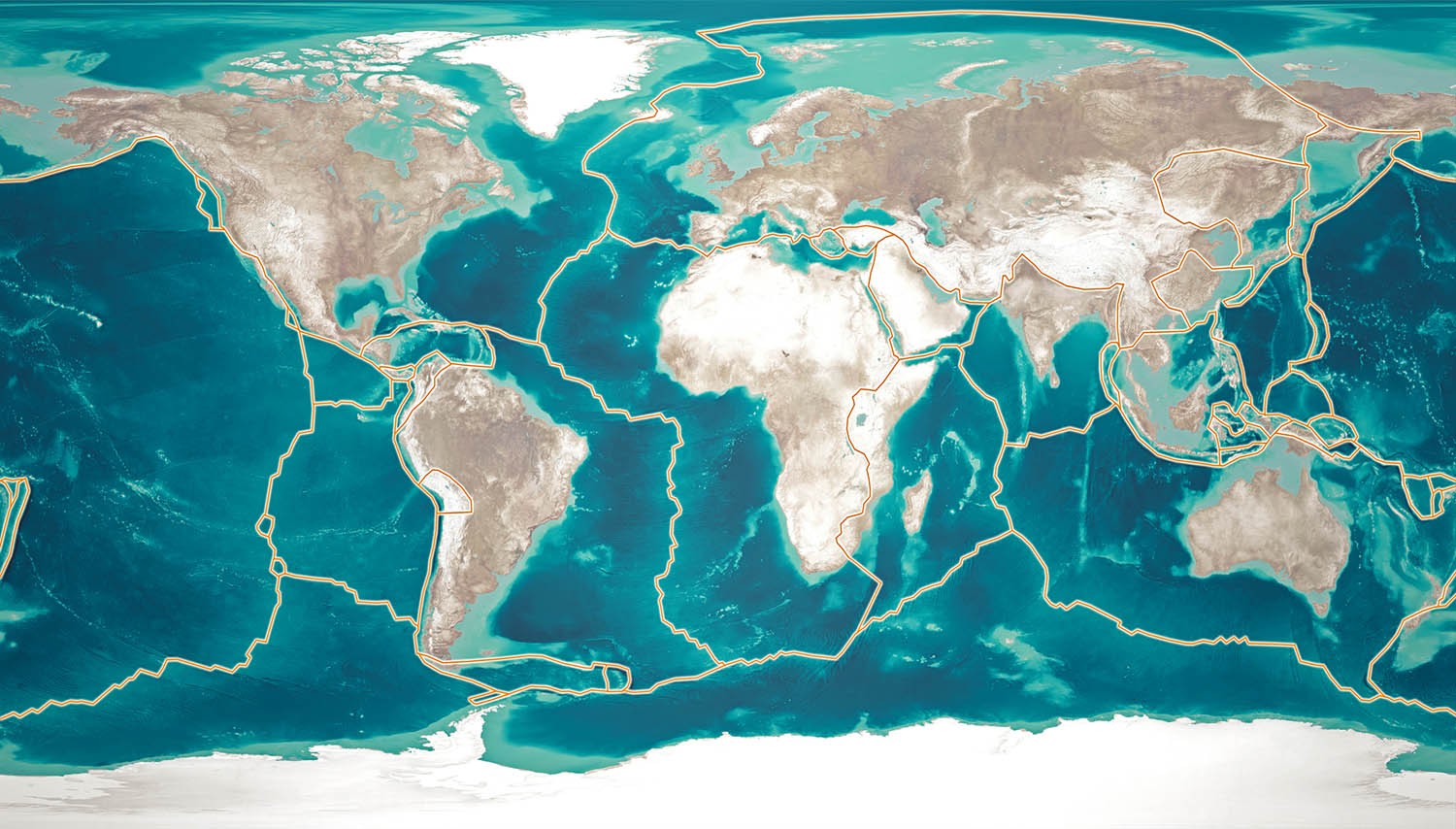

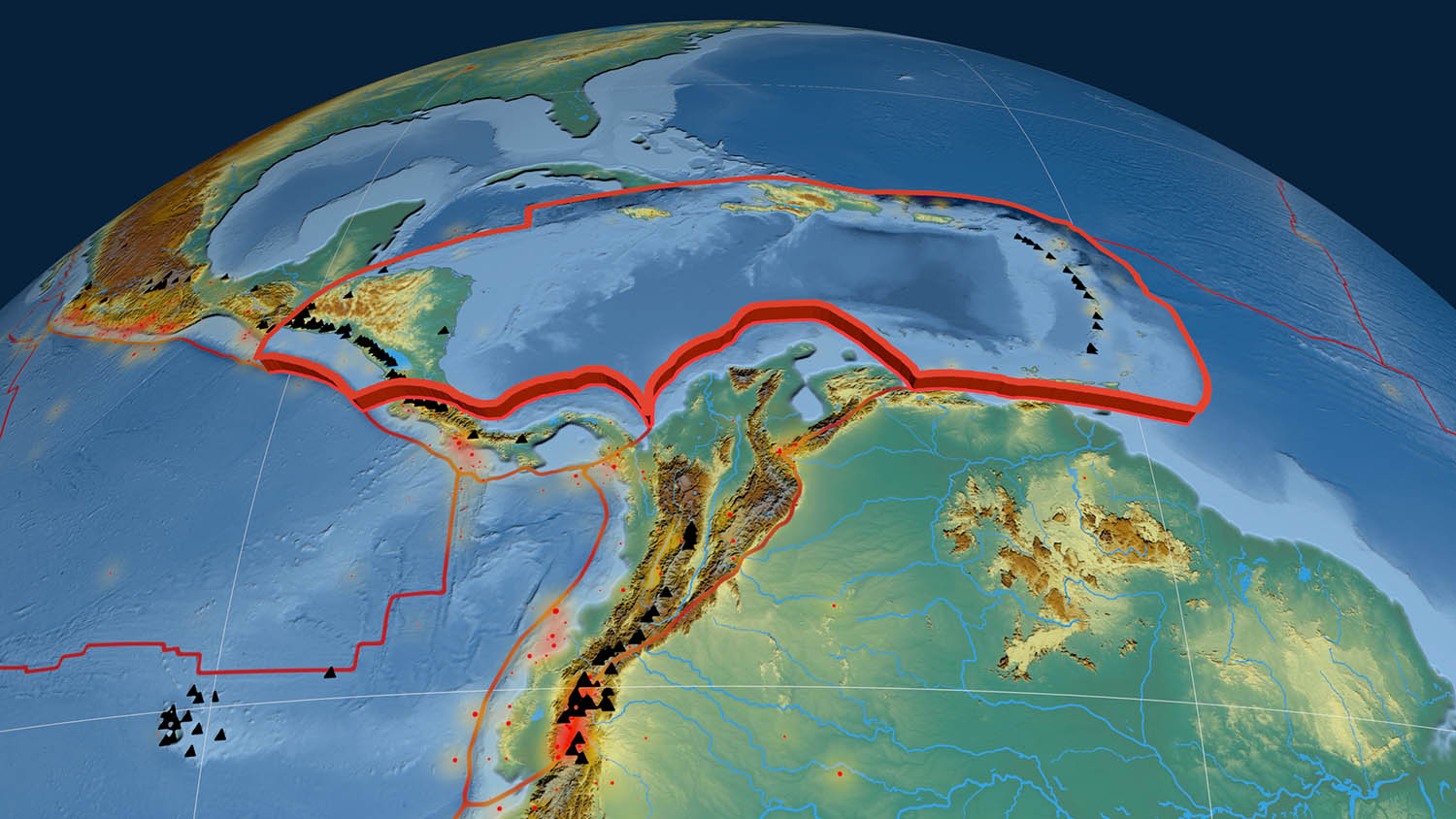

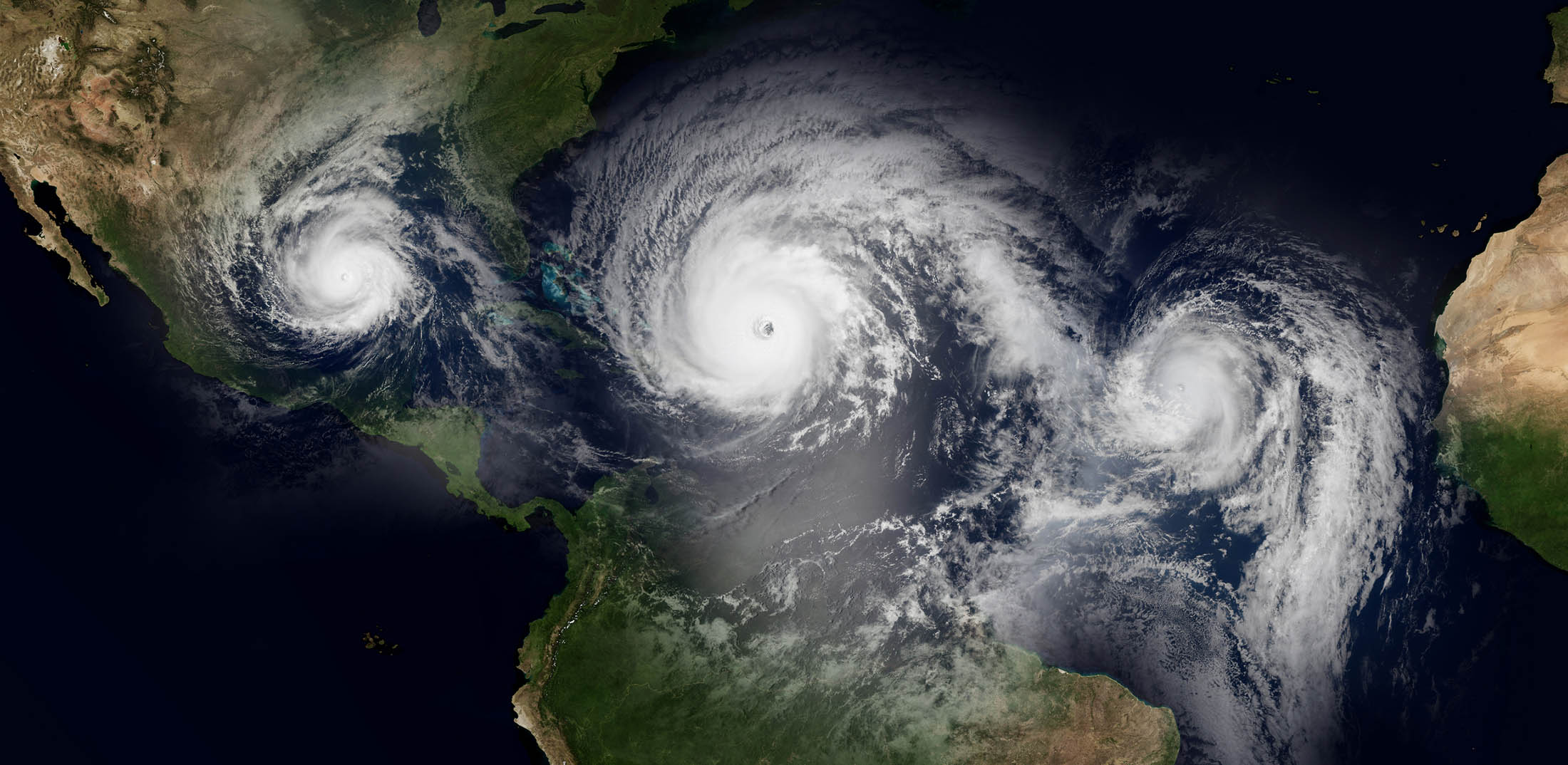

The Caribbean region’s exposure to weather hazards, precisely because it is in the North Atlantic ‘Hurricane Belt’, is well known. Less known is the fact that most major Caribbean cities and their ports are close to the active boundaries of the Caribbean Tectonic Plate.

The plate boundaries are dynamic and have a history of generating strong seismic shocks as well as tsunami waves. The volcanism associated with the subduction zones on the Eastern (Leeward and Windward islands) and Western (Central American) boundaries, have created problems in the past for shipping, port operations, and for civil aviation.

Tsunamis also affect the region and past tsunamis were associated with local volcanism, submarine landslides as well as local and regional seismic events. Distant seismic events in the wider Atlantic basin (e.g. the 1755 Great Lisbon Earthquake) have also generated tsunami effects in the Caribbean. The impact of tsunamis on the region is well documented in Caribbean Tsunamis: A 500 Year History from 1498 – 1998, Olaughlin and Lander.

The Caribbean region is thus exposed to a wide variety of hazardous phenomena, including but not confined to hurricanes. All Caribbean cultures, societies, and economic sectors have therefore had to adapt and adjust their practices in response to these many environmental threats. Coping with multiple risks and avoiding, preventing or mitigating the damage and impacts from the wide range of hazards has led to a variety of traditional, largely reactive coping mechanisms, preparedness and response measures. It should be noted that in some small Caribbean jurisdictions where there is only one modern port facility, an additional burden of national responsibility rests on the operators of that facility.

RESPONSE MEASURES

Over the centuries, Caribbean societies have evolved a raft of practices to deal with threats of natural phenomena particularly those considered ‘predictable’. Our indigenous Taina and Kalinago (formerly Carib) predecessors apparently did locate their settlements away from areas most exposed to the severe impacts of hurricanes which they believe were instruments of their powerful deity Hutacan (a.k.a. Furacan). They were observed to move their assets and people to higher ground when wind, sky and sea conditions and the behaviour of animals indicated the possibility of severe weather conditions.

These careful observations of environmental conditions by one group in the Eastern Caribbean apparently enabled them to advise their newly arrived European “guests” to secure their property and join in the move to higher ground inland. The persons conveying the warning message were however subsequently punished for practising “witchcraft”. This remains a reminder of the risks faced by prognosticators and forecasters.

Traditional largely reactive response/preparedness measures evolved over the centuries and have been mainstreamed into many aspects of Caribbean life. Based on a combination of observation and recollections of past experiences, they represent best practices from an age when warning systems were not fully developed and scientific understanding of natural processes was still emerging. Such measures did not have the benefit of today’s increasing knowledge of global climatic and geological processes.

Nonetheless, the traditional hurricane orders, relief and preparedness measures served the Caribbean well. They have proven effective in reducing some impacts of weather-related events. Examples of these practices include the formal designation of the period June 1 to November 30 as ‘hurricane season’ and the mobilization of national campaigns related to hurricane education and awareness building. Weaknesses in this approach include the fact that hurricane tips and public education campaigns largely focused attention on personal safety and household protection.

PORT PROTECTION MEASURES

The second half of the 20th century saw the evolution of improvements in weather forecasting; warning arrangements; and, delivery of new severe weather information products. These largely emerged from post World War II technologies including radar, improved telecommunications, long-range hurricane hunter aircraft and missile systems capable of launching orbital platforms to facilitate weather observations and climatic modelling. With reliable prediction of ALERT, WATCH, WARNING and ALL CLEAR phases of hurricanes and similar severe weather systems, it became possible for seaports, airports, maritime/ shipping, fishing interests, recreational marinas, tourism facilities, essential services, the public utilities as well as civil defence and emergency services to develop coordinated and synchronized response arrangements for weather-related phenomena.

Complex, sophisticated ‘Hurricane Preparedness’ plans now exist in many sectors and most modern Caribbean ports. These typically address a wide range of issues including system redundancy, facility protection, physical / structural security, back-up services, business continuity, supply chain management and port services restoration/recovery.

Harbour Masters traditionally have had wide discretionary “lead” authority to designate safe anchorage areas, deal with hazards to navigation and similar measures involving port, offshore platforms, recreational boaters, cruise tourism, commercial and artisanal fishing interests and sectors. This customary “lead” role of the Harbour Masters may need review and legal underpinning as the maritime sector is modernised in many jurisdictions.

While there is general recognition of the critical role of ports in post impact recovery, including their role in ‘humanitarian’ response, some anecdotal evidence from recent events suggests that there is room for improvement. In areas such as rapid restoration of services, management of port congestion and humanitarian logistics, structured forensic reviews and more effective experience sharing are some areas where improvements may be necessary.

In addition, Caribbean port managers, like many other managers across the region, have not yet developed seismic and tsunami sensitive arrangements which compare with those they have in place for hurricanes and weather phenomena

A significant challenge that faced all Caribbean sectors at the end of the 20th Century, was how to move on from the culture of weather and hurricane focussed preparedness to address the challenges of ‘All Hazards and All Risks’. The region should recognise that the partial successes of the Hurricane Preparedness” cycle can provide a sound platform for ramping up to modern Risk Reduction and Resilience measures.

TRENDS, EMERGING CHALLENGES

Globally and in our region, losses, particularly from extreme weather events and the primary, secondary and indirect effects of seismic hazards have been on the increase. Current projections based on credible modelling of Climate Change and Climate Variability suggest that weather-related losses will continue to rise until adaptation to climate volatility is fully in the mainstream. Factors cited as influencing the increased losses associated with Climate Change are not confined to sea level rise but include:

- The possibility of increased strength, frequency and persistence of hurricanes,

- Storms and hurricanes demonstrating rapid intensification

- Storms and hurricanes undergoing sharp changes in track speed and direction and

- Storms and hurricanes occurring outside of the normal “hurricane season”.

These apparent changes in tropical storm and hurricane behaviour have practical implications – currently and in the very near future – for all Caribbean coastal zone interests. Maritime sector stakeholders, particularly those responsible for infrastructure and coastal investments, including tourism plant, may need to address these new circumstances with innovative thoughtful responses such as appropriate reassessment of property insurance arrangements.

SEISMIC EXPOSURE

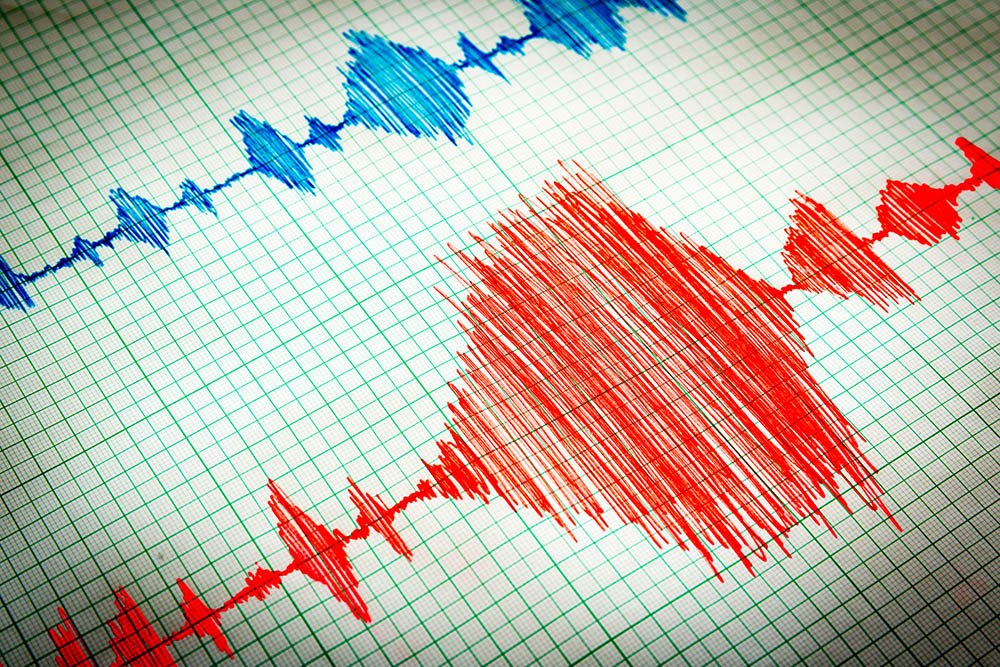

Seismic events are less frequent and do not follow as regular a cycle as the annual hurricane season. This may explain the continued neglect in the region’s planning, public safety and regulatory processes.

Formal building codes, risk zonation and appropriate capacity building are receiving the attention of several multilateral and national bodies. It is in the interest of port owners and terminal operators to participate in these programmes. Risk assessments, microzanation, vulnerability mapping and risk zoning exercises are held in several territories. In recent years, new technologies including GPS measurements have allowed specialists to focus attention on ‘locked’ tectonic plate sectors and potential seismic ‘gaps’ including several Caribbean Plate segments.

All maritime interests should thus be aware that the Caribbean region is seismically active and that civil defence and national emergency offices (and even the port insurers) may have credible scenario-building information.

Several Caribbean ports, (including St. Johns, Antigua, 1973; Limon, Costa Rica 1991; Port au Prince, Haiti, 2010) have been affected by liquefaction resulting from seismic activity. The most recent significant event, the January 2010 Port au Prince earthquake, which devastated the capital region and also had dramatic ground liquefaction impacts at the port, is well documented. That event provided serious lessons in port impacts, one of which is congestion challenges. It stimulated an interesting regional initiative, the Port Resilience Programme (PReP), which, with private sector (FedEx) support continues to be active although now confined to airport resilience building.

GROUND LIQUEFACTION

Ground liquefaction has been observed at many Caribbean locations in past seismic events and has been associated with several other modern container port complexes (e.g. Kobe, Japan 1995). The phenomenon is associated with coastal land fill, dredged material and a high water table – all common features of many port areas in the Caribbean and elsewhere.

In the course of preparing this note it was not possible to find any extensive material or inventory on the vulnerability of Caribbean Basin port complexes to this or related ground displacement phenomena. The direct, indirect, and long term loss-of-traffic impacts of the 1995 Kobe earthquake is a sobering, very well documented case with which Caribbean port operators should become familiar.

Modern container ports depend on sensitive, sophisticated lifting and moving equipment to facilitate precise container traffic movement, the economic lifeblood of such facilities. Many cases of such equipment being adversely affected by ground motion, warping, land displacement, liquefaction or simple toppling are available. Pre-arranging innovative back-up and backstopping contingencies between port operators who may be more used to competing than cooperating may be the best response for avoiding or minimising long term fall off in port traffic.

HAZARDOUS MATERIALS

Port complexes facilitate the movement of the wide range of chemicals essential to many economic sectors (agrichemicals, refrigerants, petroleum products, etc.). Spills occur during routine port operations and are very likely in the event of extreme conditions including those associated with seismic events.

In the case of a medium to large event affecting a significant urban area or a large part of the national territory, it is possible that port operators may be unable to access off-site support unless standing arrangements are made in advance.

Spills into the marine environment are also eventualities which port operators or their clients or sub-contractors need to address in continuity and resilience arrangements.

STRATEGIC APPROACHES

Addressing and overcoming these and other challenges require strategic approaches, long term “over-the-horizon” thinking, joint team action and innovative public private partnerships. Some strategies may require improvements in facility design, retrofitting, and even new policy frameworks. More robust response procedures that build upon the traditional preparedness measures but are capable of dealing with “all hazards/all risks”, (not just weather-related threats) may also be required. Ideally such improved robust arrangements should also cover spills, environmental emergencies, security incidents, health and bio-security threats.

Improvements to the traditional but limited reactive past procedures should include meticulous attention to Business Continuity, Supply Chain and Enterprise Risk Management methodologies along the lines of the emerging cluster of ISO Risk, Supply Chain and Business Continuity Standards (ISO 31000; ISO 22301 etc.).

Fortunately, new knowledge, improvements in technology; the structured methodical use of post impact forensics and the systematic sharing and application of lessons from recent (global and regional) events are available to drive the transition to more resilient ports. New approaches to Comprehensive Disaster Management (CDM); Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR), Resilience and Sustainability are capable of ushering in a future characterised by significant reduction in damage, disruptions, and business losses.

Global initiatives to promote resilience and risk reduction include the UN ISDR Frameworks (Hyogo 2004 to 2015 and Sendai post 2015).

While both these UN Frameworks have had broad support from Caribbean nations, many national DRR programmes have (understandably) prioritised the humanitarian, settlement, and internal mobilisation (civil defence /emergency response) components.

Port interests in the Caribbean may need to forge or improve upon existing strategic alliances with other critical infrastructure stakeholders and the private sector in order that their Risk Reduction, Response and Resilience building agendas are fully attended to and integrated into the sectoral, national and regional DRR, business continuity and resilience building initiative going forward into the 21st century.

Without resilient (air and sea) ports, national efforts to improve corporate and sectoral business continuity systems, effective recovery arrangements, supply chain protection and to ensure timely humanitarian response are unlikely to succeed. []

- First published: June 1, 2016.

* Franklin McDonald, currently (2016) a Visiting Scholar at York University Toronto, Canada, is an Engineering Geologist. Former Head of Jamaica’s focal points for Earth Sciences, Disaster I Emergency Management, and Environmental Conservation; he has several decades of experience in Wider Caribbean Risk Reduction and Resilience Building Initiatives and has served as Vice Chairman of Jamaica’s National Council of Ocean and Coastal Zone Management (NCOCZM). Contact: franklinjmcd@gmail.com