On a path of death and destruction

By Mike Jarrett

2017, November 1: This was not a particularly hot summer. Certainly nothing like the previous year, 2016 which, as the US Government’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reported, was one of the hottest on record. Yet it turned out to be one of the most tragic for many Caribbean nations.

The NOAA reported that the combined average temperature over global land and ocean surfaces for August 2016 was the highest for August in the 137 years that data have been recorded. And, according to the agency, it was the sixteenth consecutive month of record warm temperatures on Earth. The August 2016 temperatures surpassed the previous record, set in 2015.

August 2016 was also the highest monthly land and ocean temperature departure since April 2016 and tied with September 2015 as the eighth highest monthly temperature departure among all (the 1,640) months on record. Fourteen of the 15 highest monthly land and ocean temperature departures in the record have occurred since February 2015, with January 2007 among the 15 highest monthly temperature departures, the NOAA reported.

The NOAA’s report about record-high temperatures stood in stark contrast to the scepticism of a few, including the eventually aspirant for the White House top job, who argued that climate change (and global warming) was a hoax. But the scientists were reading statistics that showed, in the period June to August, the Earth’s average temperature was significantly above the average for the 20th Century.

Having endured a hot summer in 2016, it was with some relief that Americans welcomed a comparatively cool summer in 2017. Cooler, perhaps, but temperatures in July this year were still above the 20th Century average (by 2.1oF.). And, although cooler than 2016, July 2017 was the tenth warmest (July) in 123 years of record-keeping.

Harvey arrives

NOAA had not yet documented figures for August, indeed, August was barely half way through when a depression emerged from a tropical wave to the east of the Caribbean’s Lesser Antilles. That depression gained strength and, by August 17, it was officially declared a tropical storm and given the name Harvey. It was the eighth named storm for 2017.

Tropical storm Harvey crossed the Windward Islands on the following day, following a path just south of Barbados, thrashing St. Vincent and the Grenadines with gale-force winds, as it entered the Caribbean. In a matter of days, Harvey became the first major hurricane of the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season.

The system lost energy for a while; weakened to a tropical wave by August 19; continued on a north-western path across the Caribbean; regained strength by August 23 and in 48 hours was again a Category 4 hurricane headed for the US mainland with the state of Texas in its path. The first hurricane to hit the US mainland in 12 years, Harvey smashed southern Texas, dumping more than 50-inches of rain, enough to flood and demolish much of Houston and adjacent areas; moved back into the Gulf of Mexico; gathered more energy; and, headed for Louisiana. By the time it started to weaken and head north, Harvey had inundated hundreds of thousands of homes; displaced some 30,000 people; left at least seven dead and had ravaged towns and cities across 300 miles of coastline.

Meanwhile, as Harvey started its devastation of Texas, a tropical wave over western Africa came to the attention of the US National Hurricane Center (on August 26). That tropical wave strengthened over the next few days and by August 30, a new tropical storm, Irma was the topic of discussion by meteorologists on all television networks in the hemisphere.

Massive Irma

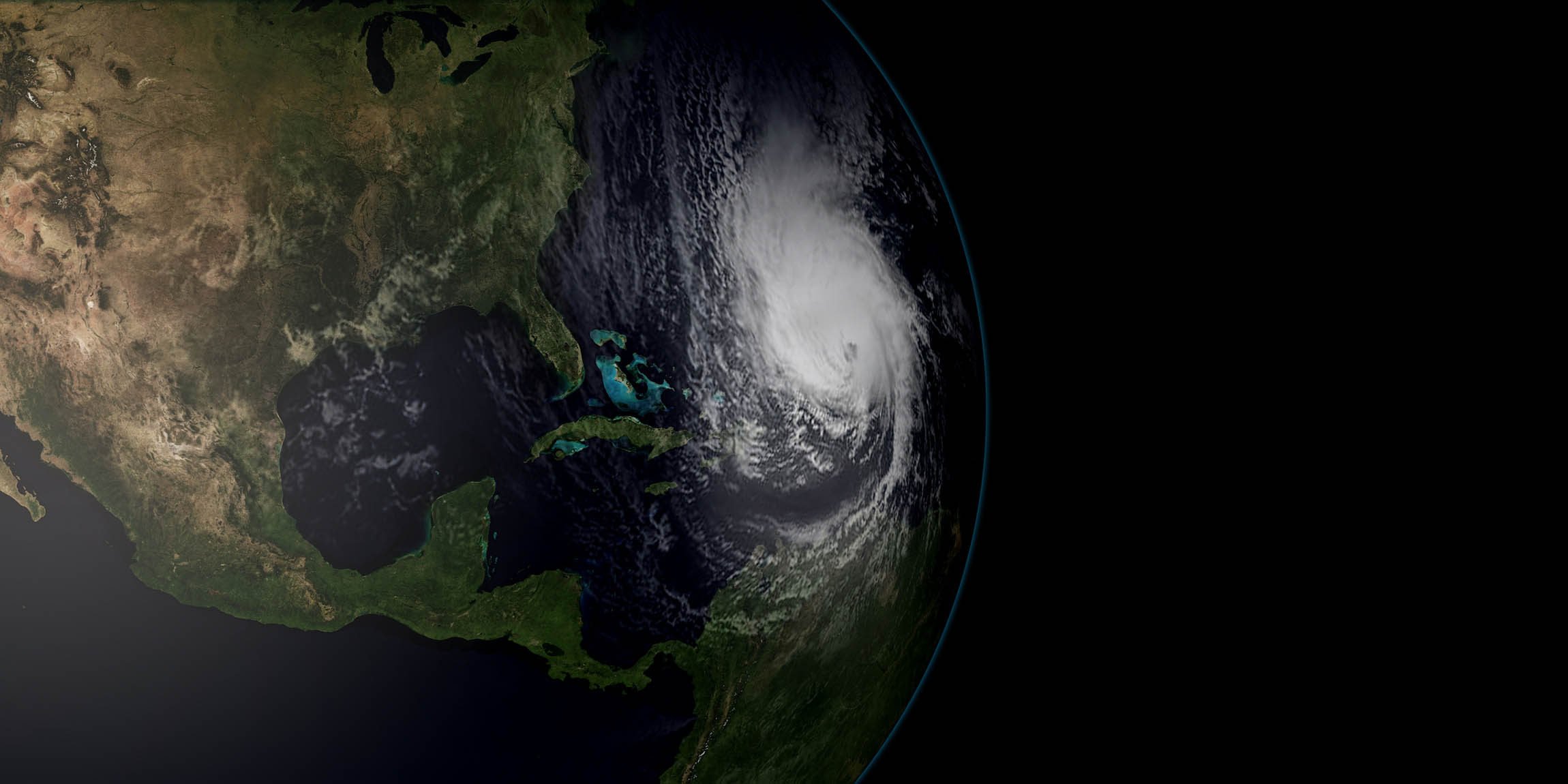

Irma was declared a Category 2 hurricane within 24 hours of its naming and in short order was upgraded to Category 3. It held this intensity for a few days and, on September 4, 2017, became a massive Category 5 hurricane, one of the largest weather systems the Atlantic had ever experienced and, at the time, the strongest tropical cyclone on Earth. All weather models projected a path that would bend northwards towards the Florida peninsula via the northern Caribbean.

Irma was declared a Category 2 hurricane within 24 hours of its naming and in short order was upgraded to Category 3. It held this intensity for a few days and, on September 4, 2017, became a massive Category 5 hurricane, one of the largest weather systems the Atlantic had ever experienced and, at the time, the strongest tropical cyclone on Earth. All weather models projected a path that would bend northwards towards the Florida peninsula via the northern Caribbean.

Irma hit the north-eastern end of Cuba as a ‘Cat 5’ beast, late on Friday, September 8. It ravaged about 800 Km (500 miles) of coastline including the Camaguey archipelago. Havana was flooded and Varadero and other coastal towns were hit by a storm surge which some estimates put at well over 6 metres (20 ft.). Seawater penetrated as far as 500 metres inland, in coastal districts between the Almendares River and Havana Harbour. The Malecon was submerged. Irma lost some energy in its Cuban onslaught, dropping to Category 3, leaving 10 persons dead and hundreds of thousands distressed and homeless.

True to the meteorologists’ projections, Irma, having regained strength over the warm waters between Cuba and the Florida Keys, headed for Florida, its breadth wider than the peninsula. It made landfall at Cudjoe Key with maximum sustained winds of 215 Km per hour and continued across the Florida Keys northwards, the eye moving up the eastern side of the peninsula. By the time it made its second landfall, hitting Marco Island on September 9, Irma had weakened to a weakened to a Category 2 before eventually dissipating overland across several southern states.

So massive was this Category 5 hurricane, it caused catastrophic damage, to various degrees, in several countries and territories, including: Anguilla, Barbados, Barbuda, British Virgin Islands, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Florida, Haiti, Puerto Rico, Sint Maarten, St. Martin, the US Virgin Islands, the Turks and Caicos Islands. Indeed, Barbuda’s housing stock was so damaged, inhabitants of the island had to be evacuated.

No way, José

José became the third major hurricane of the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season. However, compared to the others, it left behind few horrors.

It came to attention on August 31 as a tropical wave just leaving the west coast of Africa, heading across the Atlantic. Before the end of the first week of September, it had gained respect and by September 8 it was rated Category 4.

At first meteorologists plotted a path similar to that taken by Hurricane Irma. It was expected to batter territories that had still not yet recovered from Irma’s wrath. But, José did not go that way. Instead, over the next two days, it lost much of its energy. On September 10 it started showing signs of disintegration and four days later lost its hurricane status. This was not for long. By September 16 José started on a northerly track and had intensified enough to regain hurricane status of Category 2.

Even before José bundled northwards, its path taking it to the East and away from the US coastline out into the Atlantic, a new system had caught the eyes of meteorologists.

Then came Maria

It was September 13 and scientists at the National Hurricane Centre had become interested in a tropical wave that would ultimately leave 59 fatalities and horror stories aplenty on its path of death and destruction.

It was September 13 and scientists at the National Hurricane Centre had become interested in a tropical wave that would ultimately leave 59 fatalities and horror stories aplenty on its path of death and destruction.

Named a tropical storm on September 16, this massive cyclone was, in a matter of two days, to become the seventh hurricane of the 2017 season and the second Category 5.

Hurricane Maria left behind serious damage and loss of life in a number of Caribbean territories and, particularly, in Dominica, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Guadeloupe, Haiti, Martinique, Saint Kitts and Nevis; Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands, Turks and Caicos Islands; and, extensive flooding in other territories including Barbados.

On September 18, just two days after becoming a tropical storm, Maria had taken on the definition of a Category 5 hurricane and was now packing sustained winds howling at 260 Km/h (160mph). It hit Dominica that night with the full force of a Category 5 hurricane, destroying infrastructure and residential housing and, in the process, taking 27 lives.

On September 18, just two days after becoming a tropical storm, Maria had taken on the definition of a Category 5 hurricane and was now packing sustained winds howling at 260 Km/h (160mph). It hit Dominica that night with the full force of a Category 5 hurricane, destroying infrastructure and residential housing and, in the process, taking 27 lives.

It was the worst hurricane to hit Dominica in that country’s recorded history.

The capital, Roseau was smashed. There was hardly a structure with a roof. And all but an occasional electric pole was either down or broken. The port and fishing town of Marigot, was, by one estimate, 80% damaged.

Within this same 24-hour period, as Hurricane Maria thrashed Dominica, the people of Martinique were also feeling its overwhelming force. In Martinique, it levelled almost three-quarters of the entire banana crop; knocked out electricity and water supplies to nearly half the territory’s population and had most streets in the capital town under water. Hurricane Maria was the worst hurricane to hit Puerto Rico since 1928. It made land fall in the early hours of September 20 as a Category 4 hurricane, destroying the electric grid leaving 3.4 million without public supply. There were conflicting reports about the number of fatalities, some putting it at 16 dead; other reports, at over 20.

Flood waters were waist-high in San Juan streets as Hurricane Maria devastated the housing stock, leaving whole communities completely homeless. The territories agricultural sector was devastated. Some estimates put total damage at 80%.

Flood waters were waist-high in San Juan streets as Hurricane Maria devastated the housing stock, leaving whole communities completely homeless. The territories agricultural sector was devastated. Some estimates put total damage at 80%.

Help was slow in coming from the US mainland. A week after the event, with Puerto Rico’s citizens scrounging for food and water, the Governor, Ricardo A. Rossello declared that the US territory was fast heading into a “humanitarian crisis”. He pleaded with Washington to urgently send emergency assistance, even as the death toll mounted… people dying in the aftermath of the hurricane.

The 35-metre Guajataca Dam sustained structural damage during the passage of the hurricane. It was deemed to be unsafe and that it could possibly fail. By September 23, some 70,000 residents, by some estimates, were ordered to evacuate the area that could be affected if the dam failed. As cracks developed in the dam wall, tens of thousands of people who were directly at risk were evacuated, even as water from the 90-year-old dam poured through the towns of Isabela and Quebradillas.

The 35-metre Guajataca Dam sustained structural damage during the passage of the hurricane. It was deemed to be unsafe and that it could possibly fail. By September 23, some 70,000 residents, by some estimates, were ordered to evacuate the area that could be affected if the dam failed. As cracks developed in the dam wall, tens of thousands of people who were directly at risk were evacuated, even as water from the 90-year-old dam poured through the towns of Isabela and Quebradillas.

Two weeks later, as survivors scrounged for food and clean water, most in darkness because of the destruction of electrical generating capacity, the death toll in Puerto Rico continued to rise and was estimated at 45 persons, almost three times the number initially reported.

And then Nate

By October 3, as (90%, by some crude estimates, of) the people of Puerto Rico, still without food, water or electricity, were desperately trying to stay alive, a weather system that was to become the ninth hurricane of the 2017 hurricane season, was taking shape. Unlike its forerunners that took form off the West coast of Africa, Nate, as it was ultimately named, was forming in the south-west Caribbean. In less than 48 hours it gained tropical storm intensity and moved northwards, briskly. Drifting westwards along its northerly path, Nate made its first landfall along Nicaragua’s Caribbean shore.

It crossed Honduras; intensified as it travelled across the deep, warm waters of the Cayman Trench, threaded a path through the Yucatan Channel on October 7 and entered the Gulf of Mexico packing winds of 150 Km/h.

Nate was not the most powerful of the 2017 season’s hurricanes but it certainly was the fastest moving. It was said to be the fastest moving storm ever recorded in the Gulf. It crossed the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico in about four days, racing towards the south coast of the US mainland. It made landfall at the Mississippi River delta, near to the Louisiana-Mississippi border as a Category 1 hurricane, its path bending north-eastwards as it continued overland across the state of Mississippi.

As it headed North along the eastern seaboard of Central America, Nate left a path of destruction and death across eight countries, including Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Guatemala Honduras, Cuba and the USA. At the time of writing, the weakest hurricane of the season had reportedly left 45 fatalities on its path through the region.

The Caribbean peoples are used to tropical hurricanes, even ferocious ones. This is a feature of life in the summer. Tales are many about the destruction caused by previous hurricanes. However, given the extreme devastation of 2017, with whole countries having to be abandoned, this may be the year that they, like so many of their compatriots in the Gulf states, would like to forget. []

* National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, science agency within the USA Department of Commerce.