When it gets rough the port facility manager is the key

By Steve Cosham *

2018, February 1: With Hurricane Season only a few months away, there are many lessons from last year’s disastrous events that should serve us well.

Countries of the region need to be prepared, not just for hurricanes, but also for earthquakes, tsunamis, droughts and other natural disasters. We also need to be prepared for manmade disasters, such as aircraft crashes, oil pollution, cruise or cargo ship groundings, or accidents which could result in mass evacuation that overwhelm available resources. One such event could potentially bring 5,000 and more persons (passengers and crew) ashore to be immediately accommodated and subsequently flown out or put on another ship.

More and bigger cruise ships are ‘good news’ for national economies. Throw into that equation a major hurricane that causes severe damage to the cruise ship terminal and/or other port facilities and the country is no longer an ‘attractive destination’ until repairs are completed. The steady increase in the size of fleets and number of vessel calls are widely-used economic growth indicators. However, with growth comes deepening economic dependency as the pool of local services and suppliers increases and expands accordingly.

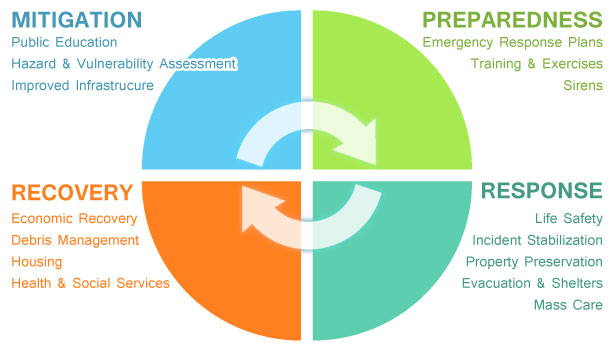

The diagram included in this essay (i.e., the Disaster Management Cycle) illustrates that we are all in this together. Not only does each territory have to identify and include all of its community partners in developing plans to mitigate and prepare for the effects of natural and manmade disasters, as a region we also need to come together, across all of the various industries, to share best practices. The lessons learned from practices that did not work as expected must be shared, if we are to maximise results from capital expended to protect people and investments from devastation and disaster.

Hurricanes, earthquakes, tsunamis and droughts are inevitable, and there is nothing we can do to stop or prevent them. But, we can take a proactive approach by treating natural disasters as hazards. By treating them as hazards that inevitably occur, we prepare differently and are therefore always in ‘ready mode.’ This translates to effective and speedy responses and, ultimately, quick recovery of operations and revenue flows.

Four phases

The disaster management cycle has four phases. It begins with the Mitigation phase, in which we identify what measures are to be implemented to limit the effects of the disaster. Next is the Preparedness phase, which identifies specifically what must be done to plan for the disaster. After the disaster occurs, we move into the Response and Recovery phases.

In practice, true mitigation and preparedness do not occur until after the country has suffered the effects of the disaster. The hurricane season of 2017 triggered a massive multi-national and multi-agency humanitarian response to the region.

If we take the time to sit down and analyse those response and recovery initiatives, as was done in the inaugural PMAC – Portside Port Management Workshop in Panama City in January 2018, we may reveal lessons about how to mitigate and better prepare for the next hurricane season and what mitigation strategies we need to employ; the intention being to reduce the need for a massive and costly response.

If response initiatives are reduced (in size and complexity) then recovery time can be drastically reduced. By reducing recovery time, we can get back to normalcy (or as the ‘new normal’ allows), then revenues will flow again.

Therefore, the business case for spending money on mitigation and preparation efforts is in reducing or minimizing the recovery time, so that revenue flows are as unaffected as possible.

Humanitarian Aid and Disaster Relief, or HADR as it is known, will arrive first by air (providing the airports and seaports are, at least, semi-functional). Although the first flight is a welcome sight and a morale booster for the affected population, there is a limit to how much cargo a C-130 airplane can carry. Depending upon the model, this can be 44,000 pounds, or eight pallets, which is about one 40-foot container.

Imperative

Aid via air is very expensive. And although disaster relief usually starts with airlift (necessary to get urgent medical and priority relief supplies to affected victims), it is unsustainable because of high costs.

The arrival of the first cargo ship marks the real beginning of substantial relief.

Containerships are rated in seven classes, the smallest being the ‘small feeder’ with a capacity of less than 1,000 teu. In Bermuda, there are small container ships servicing the country with capacity at just 350 teu. It would require 175 flight-trips by a C-130 airplane to carry the equivalent volume of cargo of just one of these small ships. This reality is why it is imperative that National Disaster Coordination Agencies (NDC) for each country include the seaports in the national planning strategy – not just as a partner but as a critical component that is essential to life.

The NDC needs to know the specifications of the port and precisely what the port can handle and what its limitations are. Bringing in a 60-ton electrical generator – where port cranes maximum load handling capacity is 30 tons and a 60-ton lifting solution is not in place – is tantamount to adding distress to calamity.

The port managers are masters at logistics and cargo handling. This they do every day. The NDC is the master of everything, at least in theory but only until they go through a disaster. This is the reason why the NDC needs to have (the) port manager/s at the centre.

The port facility manager is the key. It is the port manager on whom the agency must rely for sourcing, transporting, receiving and distributing much needed relief. The more the NDC can, in a disaster, rely upon the port facility manager to do what is, de facto, his/her everyday job, the more the NDC can focus on areas of need, and the quicker the recovery.

Hazards not disasters

This is a call to arms for port facility managers. If you are not now an integral part of the local NDC (…. and, judging by the feedback at the PMAC-Portside Caribbean workshop in Panama this past January, there is not enough engagement of seaport expertise …), please give your NDC a nudge. Agitate to have the disaster preparedness and mitigation process to begin as soon as possible. Make friends in peacetime not during conflict. Port facility managers should be ‘good friends’ with their local NDC.

There are some things in life that we can count on. One is that, ultimately, we will die. Another is that there will be another hurricane, earthquake or tsunami. But, with smart planning, we can minimise the effects of natural disasters by treating them as hazards rather than disasters.

In this mode, we can help our communities to survive and prosper. []

* Steve Cosham, Police Inspector with 36 years’ experience, currently employed by the Bermuda Police Service, holds the position of National Disaster Coordinator and National Event Coordinator. Contact: scosham2@gov.bm.