Working towards a TsunamiReady Caribbean

Is your port ready for a tsunami?

In March 2016, over 330,000 people in the Caribbean and Adjacent Regions took part in the CARIBE WAVE exercise, making it the largest international tsunami exercise to date.

By Christa von Hillebrandt-Andrade *

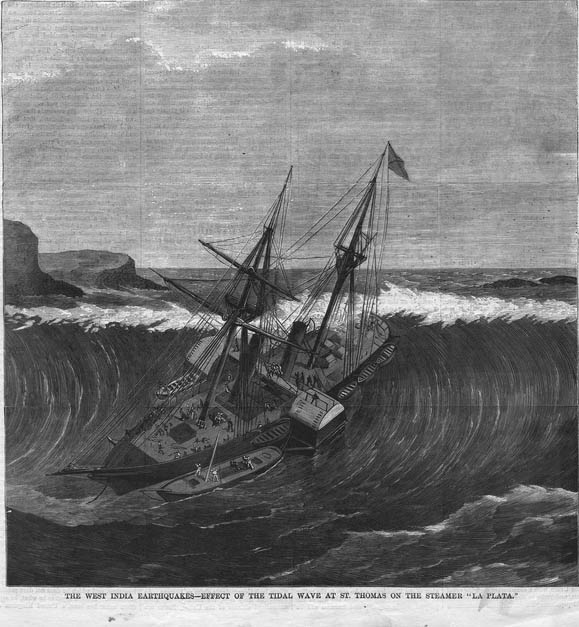

Earthquakes occur every day in the Caribbean. Most are very small and imperceptible. Once a decade, on average, a larger, stronger earthquake occurs in the region, generating a tsunami that is usually small with minimal or no impact. However, every fifty years or so, a major earthquake shakes the region and a bigger tsunami occurs and coastal areas are flooded and very strong currents are generated in ports and harbours. The largest historical tsunami occurred in 1867 in the US Virgin Islands with waves as high as 50 feet.

The last major tsunami to strike the region occurred in 1946, devastating areas of the Dominican Republic and leaving an estimated 1,790 people dead.

Saving lives and protecting national economies and livelihood is the ultimate objective of the Intergovernmental Coordination Group for Tsunamis and Other Coastal Warning System for the Caribbean and Adjacent Regions (ICG/CARIBE EWS). For just over 10 years, UNESCO, through its Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC), has helped to empower 48 countries and territories. From Bermuda to Brazil, in all the islands-states of the Caribbean and the coasts of Central and South America, UNESCO has helped to develop tsunami warning systems. In 2015, the ICG/CARIBE EWS approved programme in which UNESCO will recognize communities that have taken 2 Mitigation, 4 Preparedness and 4 Response actions to be Tsunami Ready. This programme is modeled after the successful US TsunamiReady® programme thru which 50 communities in Puerto Rico, the US and British Virgin Islands and Anguilla have been recognized.

To ‘Mitigate’ a tsunami, the hazard area must be (1) defined and (2) publicized. Scientists are continually evaluating and re-evaluating potential sources of tsunamis in the Caribbean and other regions. While most tsunamis are generated by earthquakes, a submarine landslide or a volcanic eruption can also trigger tsunamis. One of the lessons learned from the tragic 2011 Tohoku Tsunami in Japan is the importance of not under-estimating a tsunami’s potential. Many tsunami models in the Caribbean now consider the possibility of earthquakes up to Magnitude 9.

Most countries have not been able to determine what would be the height of waves along their coasts created by this and other similar events. For this reason, a default tsunami hazard zone has been proposed (called the “bath tub” approach) that covers areas up to 30 metres (98 feet) high or up to 1.6 kilometres (1 mile) inland. In areas like Puerto Rico and the British Virgin Islands, where detailed tsunami models have been run for hundreds of scenarios, it has been determined that areas of lower elevation and closer to the coast are outside of the tsunami hazard zone. But, in some cases, especially along low-lying coastal plains or up river valleys, tsunamis can advance inland more than two kilometres (1.2 miles). For boats, in addition to wave heights, currents can also be extremely dangerous. Historical events have demonstrated that tsunamis with wave heights of as little as one foot can generate swift currents – the larger the tsunami, the stronger the currents.

In order to be recognized as Tsunami Ready, along with identifying the hazard, tsunami information needs to be publicly displayed. Signs indicating areas of tsunami danger and evacuation routes must be erected. In the TsunamiReady communities of Puerto Rico, the US Virgin Islands, British Virgin Islands and in Anguilla, hundreds of tsunami signs have been installed to inform residents and visitors. Many of these are located in ports and harbours.

TsunamiReady preparedness guidelines include: (1) producing tsunami evacuation maps, (2) developing and distributing public awareness materials, (3) holding outreach or education activities, and (4) conducting tsunami exercises. Once the tsunami hazard area has been established, either using sophisticated modeling or the “bath tub” approach, the Emergency Management Authority along with the communities need to prepare a tsunami evacuation map. These maps show the evacuation areas, evacuation routes; and, areas where people can assemble in the case of an imminent threat. These maps and other public awareness materials need to be distributed using all possible media (including radio, newspapers and social media).

In addition, activities need to be organized to educate community residents, business operators and visitors about local tsunami hazards, evacuation routes and emergency communications and response. To test the level of preparedness, tsunami exercises need to be conducted. To facilitate this process, the ICG/CARIBE EWS organizes the annual CARIBE WAVE exercise. This event takes place in March. In March 2016, over 330,000 people took part in the exercise making it the largest international tsunami exercise to date.

In some places in the Caribbean it could take as little as five minutes for a tsunami to hit the shore after a major local earthquake. In the best of cases, if a tsunami is generated across the Atlantic Ocean, like what happened in 1755, Caribbean coastal communities could have as much as eight hours to get out of harm’s way. Whether five minutes or a couple of hours, warning time is very short; much shorter than for a hurricane event. Therefore, in order to be Tsunami Ready, the community must also have: (1) an emergency operations plan; and, (2) government or public authorities committed to supporting an Emergency Operations Centre. Additionally, the communities at risk need to have redundant and reliable means for (3) receiving and (4) disseminating tsunami bulletins and alerts.

The Pacific Tsunami Warning Centre (PTWC) is the official Tsunami Service Provider for the Caribbean and Adjacent Regions. It operates 24 hours a day, seven days a week. It continuously monitors seismic activity and, for larger earthquakes, determines whether there is a tsunami threat. In the event of a tsunami threat, data from over 80 sea-level stations in the region are also analyzed to further define a tsunami potential. As of 2016, the PTWC issues only tsunami information and threat bulletins for the international community. It is the responsibility of each country and its officially designated Tsunami Warning Focal Point/National Tsunami Warning Centre in each country to issue the appropriate ‘Warning’, ‘Advisory’, ‘Watch’, or ‘Information Statement’, according to national and locally established and vetted procedures. Therefore, it is very important that people who live or work in a tsunami hazard zone know the in-country procedures for receiving alerts on potential tsunamis.

In addition to the official warnings, especially for the Caribbean where tsunamis can hit shores within minutes and there will not be enough time to issue an official statement, all should be familiar with the natural tsunami warning signs: (a) a strong or unusually long earthquake, (b) a sudden rise or fall in sea level, or (c) a very strange or loud noise coming from the sea. If any of these warning signs occur, people should move as quickly as possible to high ground and as far away from the coast as possible.

Let there be no doubt, it is merely a matter of time before another tsunami strikes the Caribbean and adjacent regions. Therefore, it is imperative, indeed a matter of life and death, to ‘get ready’ and to ‘remain ready’.

The Caribbean Tsunami Information Centre, a Barbados-UNESCO partnership, as well as the NOAA Caribbean Tsunami Warning Program in Puerto Rico were established to help countries, communities and key stakeholders, like ports and harbour authorities, to get ready. UNESCO will recognize those that meet the 10 Mitigation, Preparedness and Response Guidelines as Tsunami Ready. Every country that has a marine port or harbour operation including pleasure boat marinas, is encouraged to get Tsunami Ready immediately, before the next tsunami strikes. []

- First published: June 1, 2016

_________________

References:

1 National Geophysical Data Centre / World Data Service (NGDC/WDS): Global Historical Tsunami Database. National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA.doi:10.7289/V5PN93H7[March 30, 2016])

2 von Hillebrandt-Andrade, Christa, 2013. Minimizing Caribbean Tsunami Risk, Science, Vol. 341pp. 966-968.

* Christa von Hillebrandt-Andrade is Manager of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) National Weather Service Caribbean Tsunami Warning Programme. She chairs the UNESCO IOC Inter-governmental Coordination Group for the Tsunami and other Coastal Hazards Warning System for the Caribbean Sea and Adjacent Regions. Contact: christa.vonh@noaa.gov